Part I: North Carolina’s First Prisons

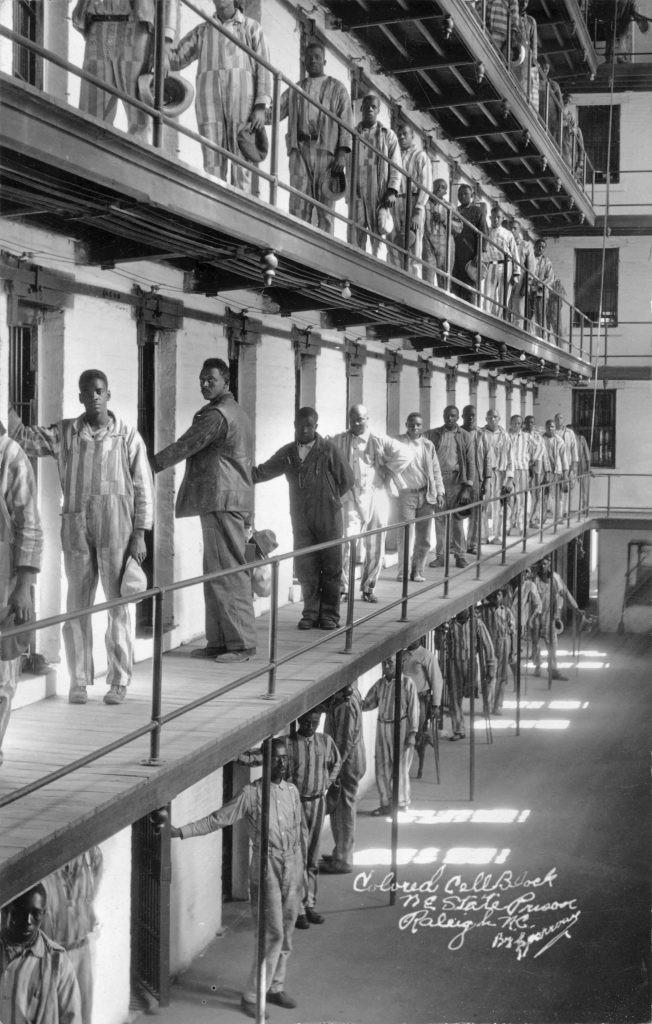

For many, imprisonment was a return to chains.

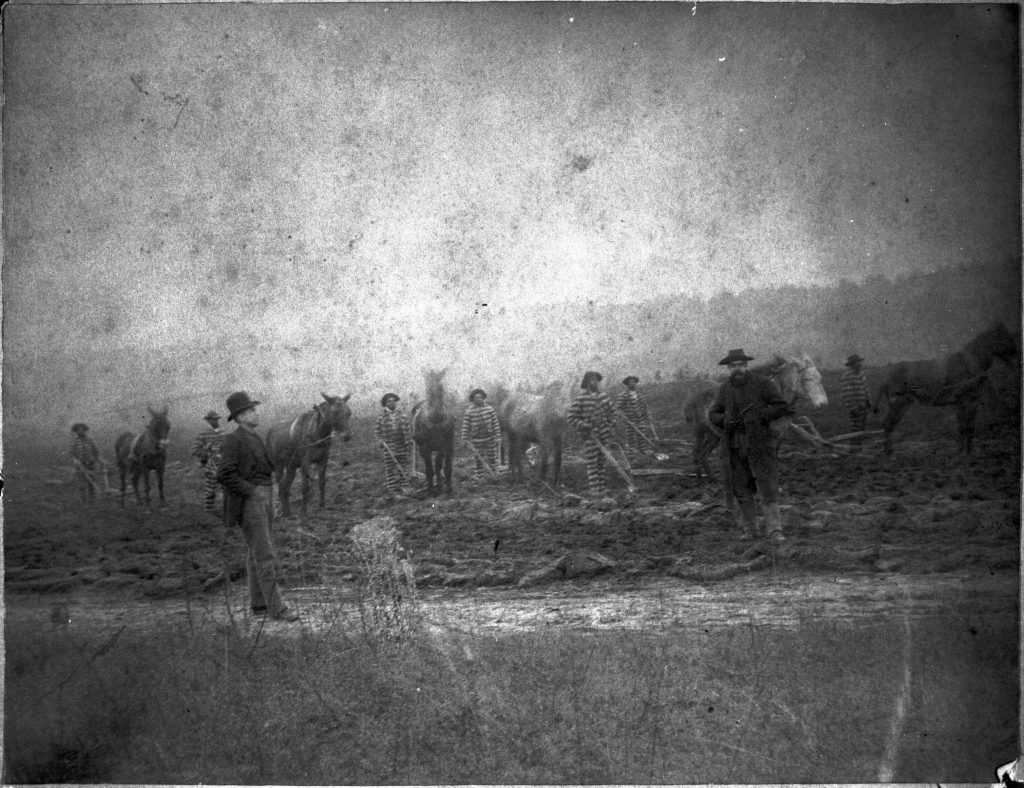

No prisons existed in North Carolina until the end of slavery.

The State put most prisoners to work. The US constitution outlawed slavery, but allowed forced labor “as punishment for a crime.”

In North Carolina, white elites supported new laws targeting Black people. It was one strategy among many they used to maintain power.

Audio Transcripts

Lonnie McPhatter and Charlie P. McMillan

McMillan: Wagram was a prejudiced town at that time. And a Black man really had a hard time in Wagram… whether he was in prison or not, he had a hard time. And there were some good people that, although they knew they were in charge, but they treat you like you were human. There was some that treated you like, you know, if you got a pet and he belong to you, so you do him like you want to do him. To me, it was like we were practically almost still in slavery.

McPhatter: We lived on Steel’s place, John Steel. And we lived there until my daddy saved up enough money to buy some land up in the Sandhills there. We used to bring cotton from up there down the road to the gin down there. The gin was called ‘W.G. Buie.’ He owned the gin, and he owned the store across from the gin. And you would come down there, and you would bring the cotton… they had a little office over there at W.G. Buie’s store where you would scale your weights in there, and they added them up or whatever… And my daddy used to come down there—you would have to borrow money at the first of the year to get your farm, but we’d wind up always finding out at the end, we were still in debt. We would, my daddy, would sell the seeds from the cotton. He would take the seeds, what he got out of the seeds, and we would buy groceries with it. The rest would go towards the debt. But we never got out of debt. And that’s how they consumed a lot of the land that the people already had. People would buy some land, and they would get to the point of debt, and then they would consume it.

McMillan: W.G. Buie owned all of Wagram just about. Buie owned the gin. He owned… the mule, the land. Everything was his. And you sharecropping, you paying for your part, and you never get out of debt. As time passed and things got a little better, they would come and say, like my daddy’s name was C.P., and they would say, ‘C.P., you just got out of debt this year. You just made it out of debt. You didn’t have nothing in the hole.’

McPhatter: So, you got to go back into debt.

McMillan: So, you go back into debt at next year’s crop. But you did make it out of debt. Of course, you used to didn’t even get out of debt. I didn’t go off to the city. Wasn’t anything here to do but pick cotton and pull corn. Top cotton in line. You work all day for three dollars a day, and that was an up-pay then. I mean, we never was given the opportunity to do nothing but what we were doing. Had they given us the opportunity to do something, we might have done better.

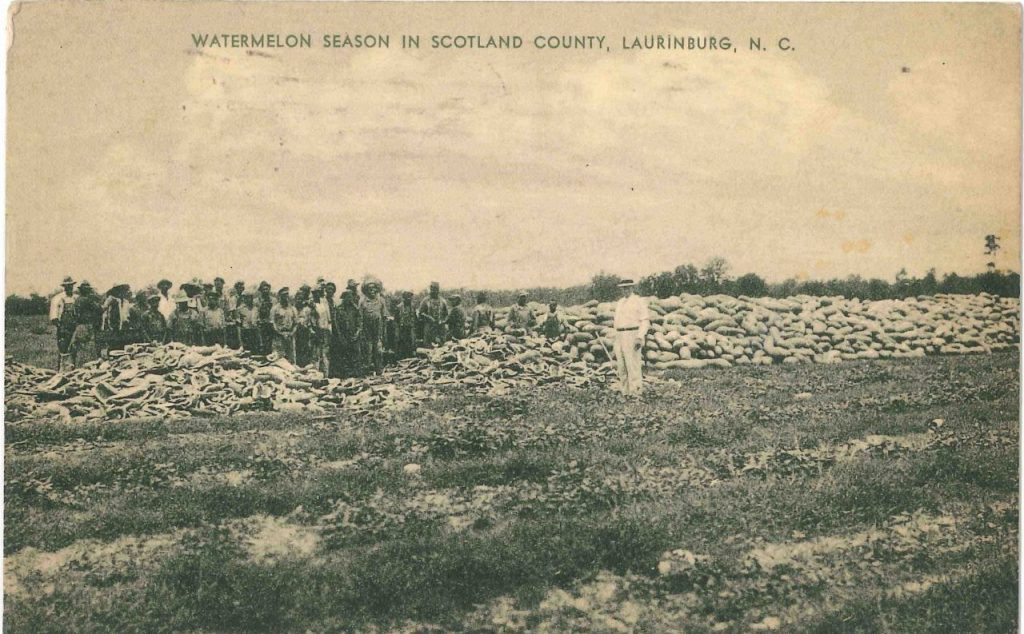

Thomas McKinnon

After the Civil War, most of the area was sharecropping even when I was a kid. My daddy ran, when I was born, a large farm, not his farm. He ran a pretty big farm that had hundreds, probably thousands, of acres. And he was what you would call, I guess you’d say ‘overseer,’ but he did the business for this lady whose husband had died. And when I was a kid, there were farmers who were partly sharecroppers then. I went around at Christmas time with my daddy when I was four or five years old, and I remember going to these little shacks back there and carrying a bag of oranges or fruit and things like that. And these people worked. A lot of times they worked as laborers partly and then had some that they farmed on a share. In other words, they got to keep a certain percent of this for their labor. But at the same time, a lot of them also had a job, and they had the bigger field, and they were paid a very minimal wage. I remember when people got paid three cents a pound to pick cotton.

The people that my daddy worked with farming, all I remember, were Black. Even when we farmed this back in the ’50’s, me and my daddy, the last year that my daddy farmed was 1960, and I was in high school. And they used to haul people out to pick cotton. They had an old school bus, and they would pick up people to come out to work in the field.

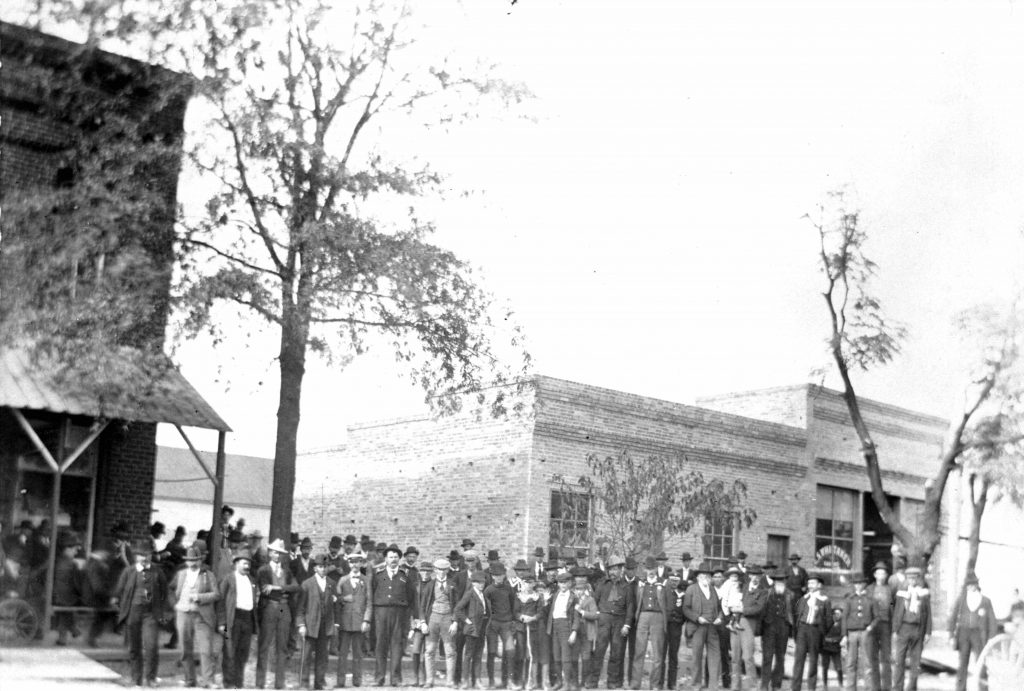

It was a farming town. On Saturday, people came in, and Wagram was thriving… had six or seven grocery stores in Wagram. Some farms actually—the W.G. Buie Company—it was a big one. They paid their workers in their fields partly in a little book that was redeemable only at the W.G. Buie Company. And some of them, actually, had a store token. Part of the salary, if you worked in the field, was this, and you could only redeem it at the W.G. Buie Company. Now, there was timber and there was other stuff, but, basically, Wagram and Gibson over here were farming towns.

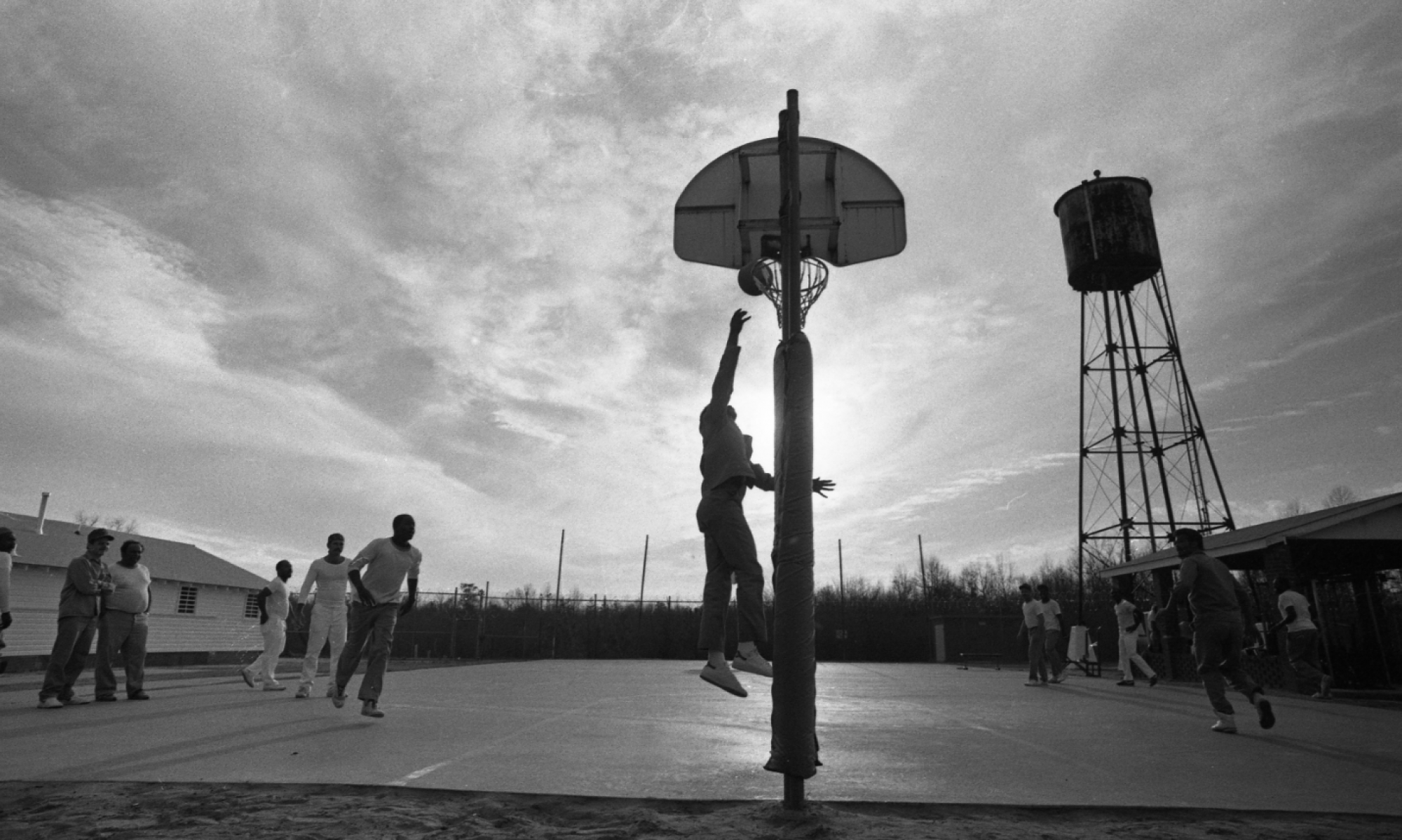

I remember prisoners working on, they called them chain gangs. Now, most of the time, they didn’t have a chain on them, but they worked out of Wagram. They had a big, long shot gun with a real long barrel, and they would have bush axes…and they cleaned the ditches and all with prison labor. All I ever saw, they were working on the road, and they would have two guards and one would be walking backwards, looking at them, and one would be on the other end, and they had a real long shotgun. I knew a guy at Wagram that killed a prisoner up there. The prisoner ran, and they fired a warning shot and then he shot and one of them shot and hit him in the head.

The crime in Wagram was petty…most of the problems probably involved alcohol. And I would say that the police in most of the time that I lived in Wagram were not free from prejudice. I could have gotten by with more than a Black kid could have… than a poor Black kid could have.