Part III: The Rise of Mass Incarceration

By the late 1960’s, Civil Rights wins had come up short on true equality.

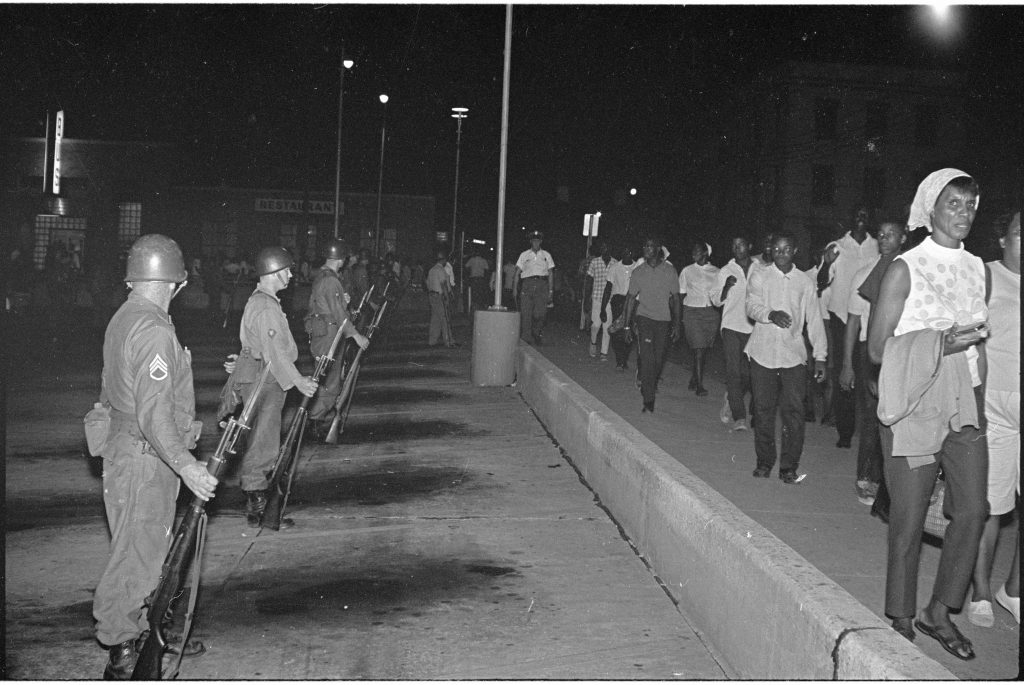

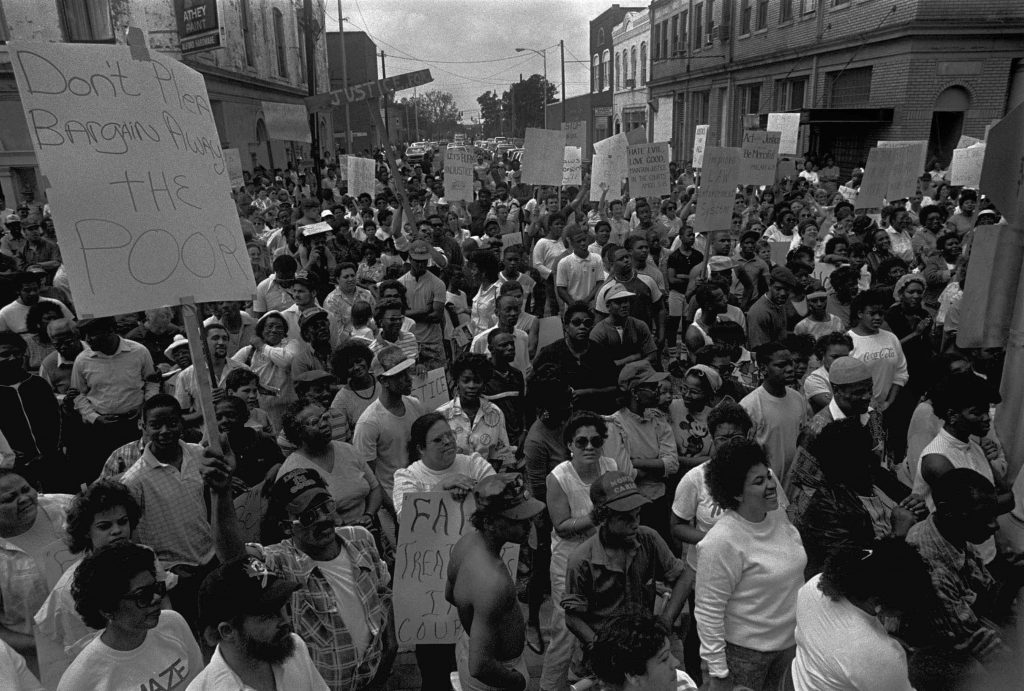

Mass uprisings erupted in response to lack of money and opportunity. Instead of ending racism and poverty, the US sent thousands more people to prison.

The War on Crime dropped like a bomb on families and neighborhoods. It hit Black communities the hardest.

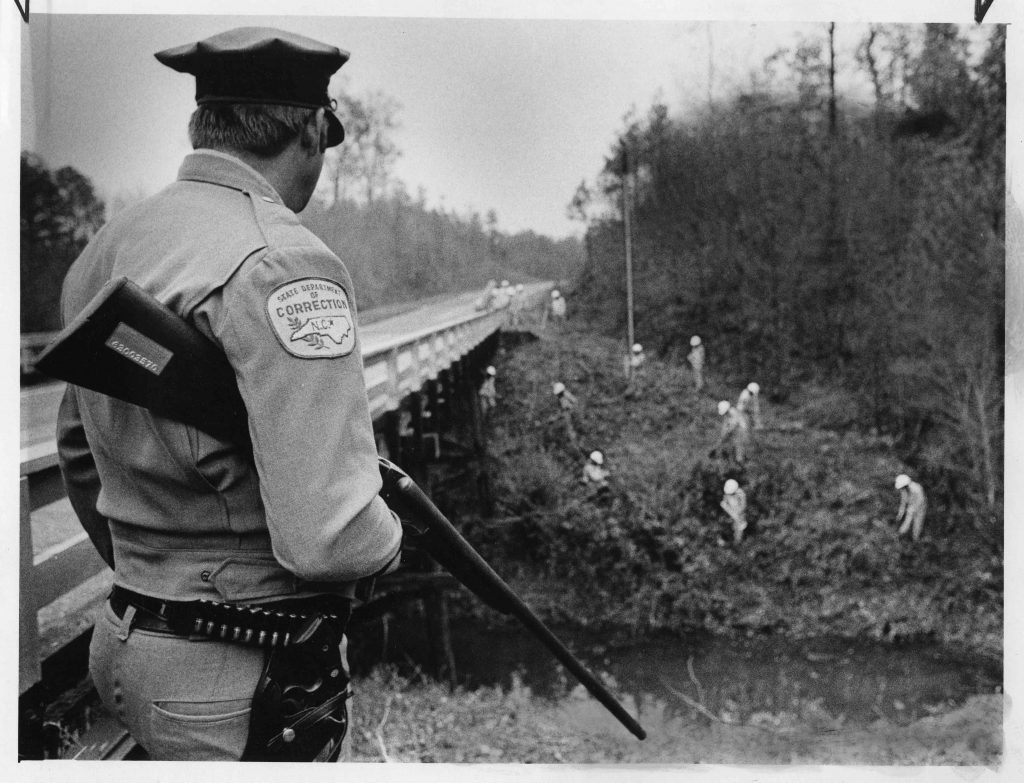

Rising numbers of prisoners worked for North Carolina.

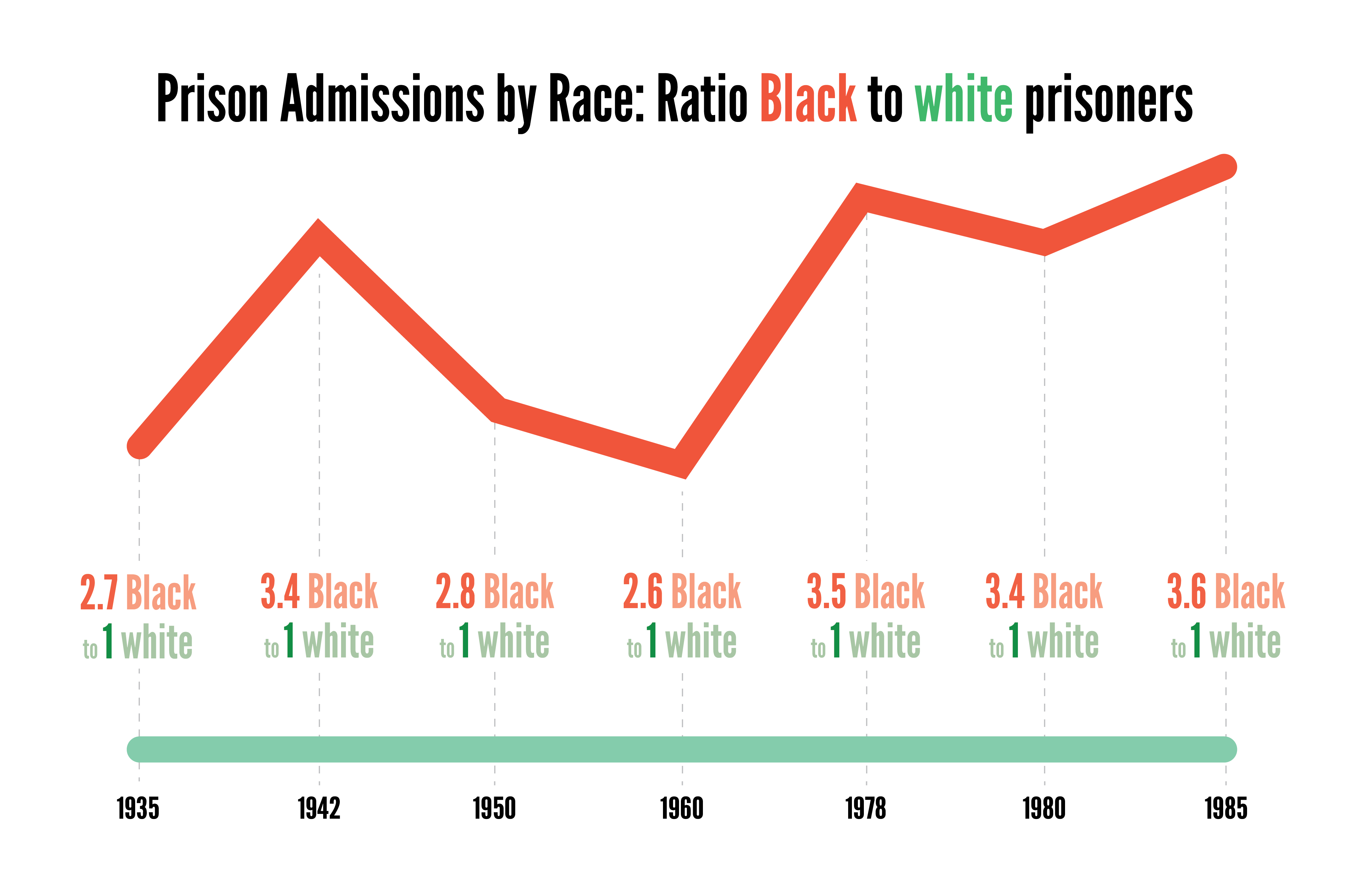

North Carolina Prison Admissions by Race, 1935-1985

Audio Transcripts

Billy Austin

Back then it was kind of tough. I didn’t graduate, and my father wasn’t around much. It was my mom. She did all the work as far as taking care of four children. And I quit school in the ninth grade. I got my GED right there where you at now in Wagram. But it was kind of tough, especially when you ain’t in school. But I did work. After that, that’s when life took a terrible turn for me. I started getting in trouble—back-to-back in jail, back-to-back in prison—but I had a tough time. You know, because basically I was living on the street young, just like a lot of these young kids around here doing these days here. I was down about probably three or four different times, and I think the last time was at Wagram…

Road squad first thing in the morning. I’m out on the road squad ‘til about 2:30, 3:00…The population—Black overpopulated then. I don’t know about now… It wasn’t no joyful ride, no matter how much good advice you get about what you going to do when you get out or how you gonna survive through this here stuff. It still wasn’t no good days. In other words, you gotta be a man—a strong person anyway—to survive.

Fifteen to thirty days in the hole for disobeying a direct order. I done that twice. And you might get two hours. You might get an hour out, maybe twice every two weeks.

The hardest part for me was the road squad. You know, because you got to go out there, and you may be picking up paper beside the road that day or whatever. You may be cutting right-of-ways. Like when I got both of my eyes swollen from wasps, that was about the hardest time for me right there. You know, was going out there and working on that road squad and coming in every day, and that’s something you got to do. If you not down there when they call your name at that fence to go out to the road squad that day, you get a major write-up and get sent straight to the hole. We even had up here in Laurel Hill, they had a ditch out there that they would dig and then it’s like one man here, one man there, one man all the way at the bottom, and the ditch was deep enough to drive the bus down into it, and you couldn’t even see the top of it. That’s how deep the ditch was.

It was overcrowded then. I mean really overcrowded. Most in there were Scotland County, and the most in there were Black, back then.

Julius Douglas

I stayed at Wagram about eight and a half years. I did 10 years all together, and back then, they would get you closer to home—so Wagram was close to Laurinburg. So, I was fortunate to get that, so I was there eight and a half years. There were no cells; there were two big dorms, ‘A’ side and ‘B’ side. I was on the ‘B’ side. But now, the only cells were in segregation—lock-up. Those were the only cells. There wasn’t a bunch of trouble. You basically did what you wanted to do. Some of the guards were cool.

At first, they were like double bunks. Then, over the years as the population started to grow, they made them triple bunks. Basically, I was the dorm man, so I kept the dorm clean. And I worked in the kitchen too. Yeah, all the food basically came from the state. Like the farm— Caledonia Farm, Odom Farm—they grew all the produce. And the cannery, that was in Raleigh. The meat, that came from Smithfield—they had a meat plant. The produce and all that was grown by the State.

I don’t know if you’ve seen [that photo of] me in that baseball uniform. We had games on Saturday. Whoever we had to play, that’s where we would go, or they would come to us. If we had away games, we would go. If we had home games, they would come to us. They would play on our field. I don’t know how many state championships we went to. We went to a few.

Wagram, there were the fences—guard towers. I mean, it really wasn’t very far you could go. When you walked, you walked around the fence, and people had walked so many years around that fence, it was like a path. That’s the only place you could walk…Oh they want you doing something. The space was very limited, you know.

There wasn’t that many white boys—mostly Indian and Black… Well, the captain he never did come on the yard…he never did come on the yard. But Lieutenant Litram, he was…he just picks. He’d walk around with that cigarette in his mouth, and it don’t fall out. Sometimes they ask him when it fall out. He walked around with that cigarette in his mouth all day. And he will find stuff to mess with you about.

Disciplinary action. They determine, whatever you did, what would be the punishment. Would you just get a write-up and lose privileges, or if it’s serious enough, then they could either keep you there or ship you somewhere else.